|

edit SideBar

|

Stromboidea

Original Description of Strombus gigas by Linnaeus, 1758:

- "S. testa labro rotundato maximo, coronata ventre spiraque spinis conicis patentibus. ... Testae color internus vividissimus."

Locus typicus: "In America" (Linnaeus, 1758); Montego Bay, Jamaica (Clench & Abbott, 1941)

Types: Strombus samba Clench, 1937: holotype Museum of Comparative Zoology MCZ 116054

Linnaeus cited

- Bonan. recr. 3. t. 321.

- Gualt. test. 33. f. A.

History and Synonymy:

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758: 745) (Strombus)

- Syn.: Strombus canaliculatus Burry, 1949: 106-108

- Syn.: Strombus horridus M. Smith, 1940: 131

- Syn.: Strombus lucifer Linnaeus, 1758: 744

- Syn.: Strombus (Eustrombus) gigas pahayokee Petuch, 1994: 82, pl. 20 fig. c (†) [nomen nudum]

- ? Syn.: Strombus nidus aquilae Vernus, 1892: 651

- Syn.: Strombus samba Clench, 1937: 18-20, pl. 1, fig. 1

- Syn.: Strombus verrilli McGinty, 1946: 46-48, pls. 5-6

pre 400 b.c.

Trumpet with engraving of a man in a diving position and a fused figure of a human face and a feathered serpent (Quetzalcoatl), Olmecs culture, Tabasco, Mexiko; Coll. Victor Landa

1610 (about)

Jacob de Gheyn II (1565-1629): Neptune and Amphitrite, about 1610, Oil on canvas, 103,5 x 137 cm Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

Lobatus gigas on de Gheyn, 1610

1758

Original Description of Strombus Lucifer by Linnaeus, 1758, p. 744:

- "S. testae labro antice rotundato integro, ventre dupliciter striato, spira carinata: tuberculis superioribus minutis."

- Locus typicus: "Habitat ad Americam australem."

- Linnaeus cited

- Bonan. recr. 3. t. 303, 304.

- Barrel. rar. t. 1327. f. 7.

- Argenv. conch. t. 17. f. E.

- Klein. ostr. t. 4. f. 85.

- "Differt a sequenti testa minus crassa, & imprimis spinis spirae minimis, nec magnis crassis pollicaribus ut in illa."

1843

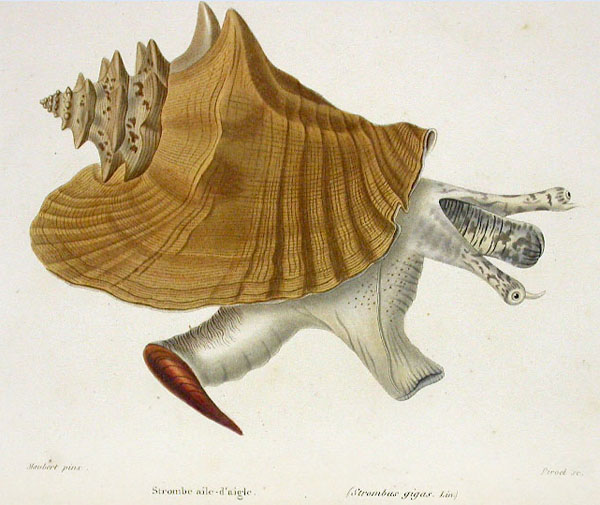

Strombus gigas in Kiener, 1843

Strombus gigas juvenile in Kiener, 1843, pl. ?, fig. 1

1844

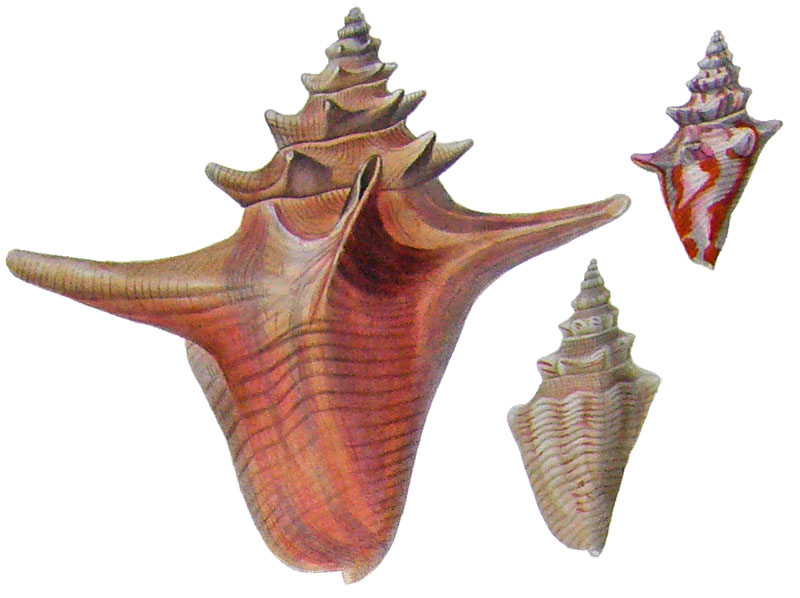

Strombus gigas in Duclos in Chenu, 1844, pl. 1

Strombus gigas in Duclos in Chenu, 1844, pl. 2

Strombus gigas in Duclos in Chenu, 1844, pl. 3

Strombus gigas juvenile in Duclos in Chenu, 1844, pl. 28, fig. 1, 2, 3

Strombus gigas in Duclos in Chenu, 1844, pl. 28, fig. 5

1850

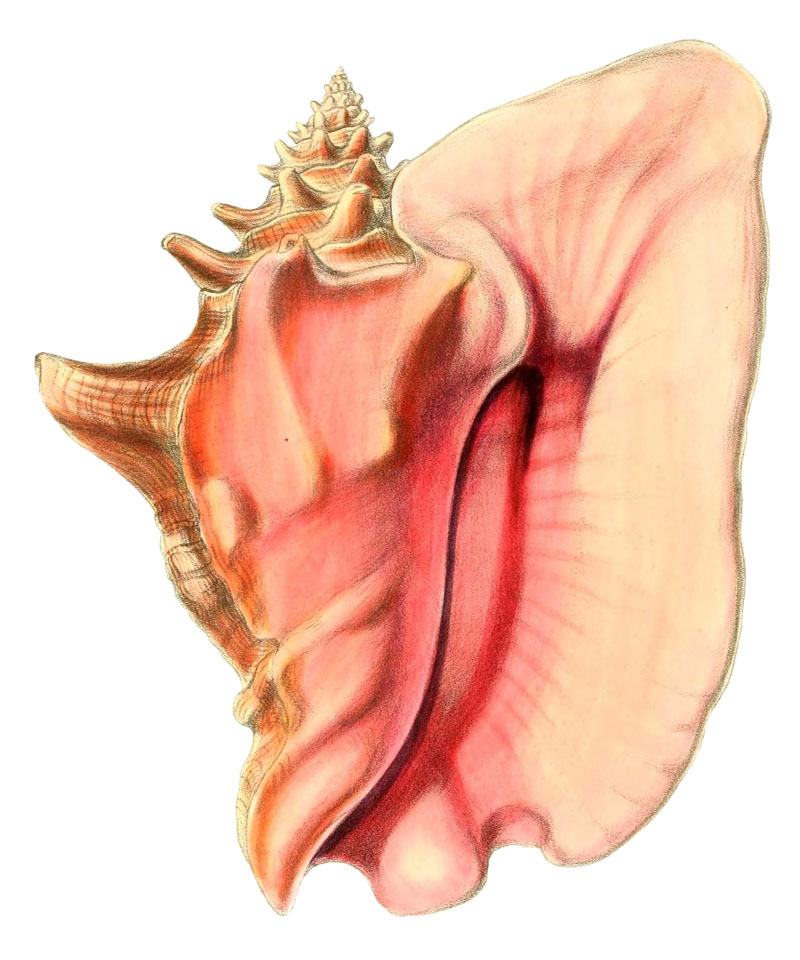

Strombus gigas in Reeve, 1850, Strombus, pl. 2, fig. 2

1887

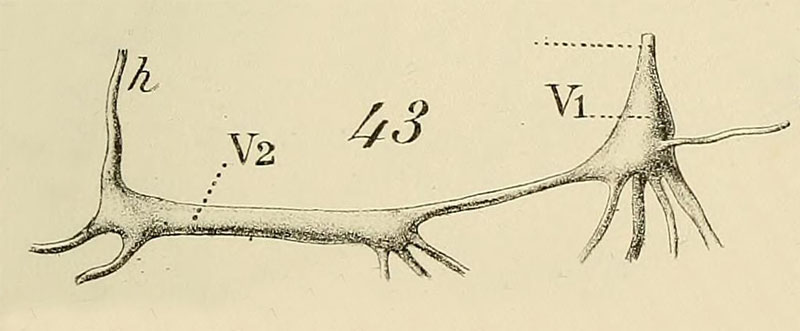

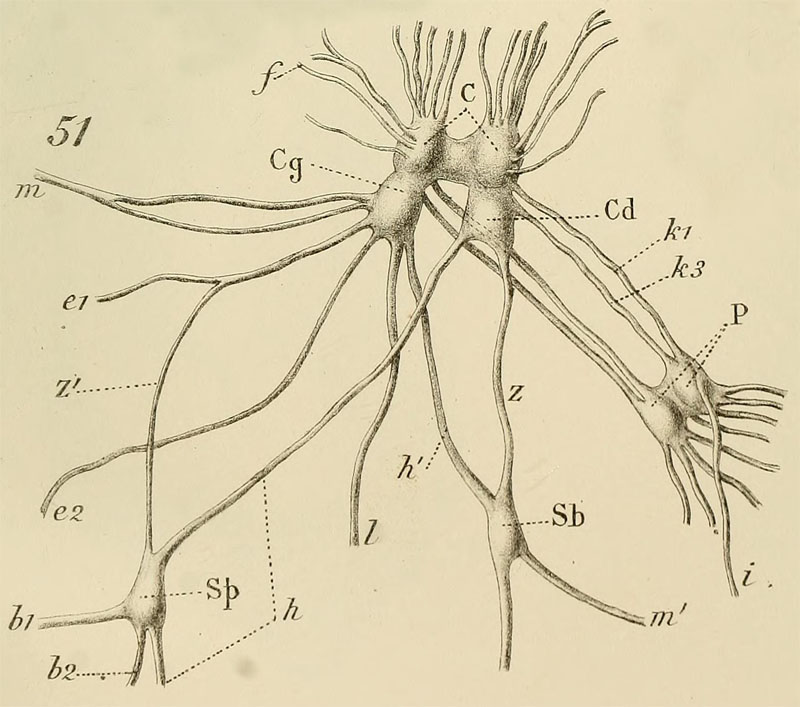

Bouvier, E.L. 1887: Pl. 9, Fig. 43. Strombus gigas. Ganglions viscéraux.

Bouvier, E.L. 1887: Pl. 11, Fig. 51. Strombus gigas. Ganglions viscéraux.ème nerveux général, à l'exception des ganglions viscéraux et buccaux.

1895

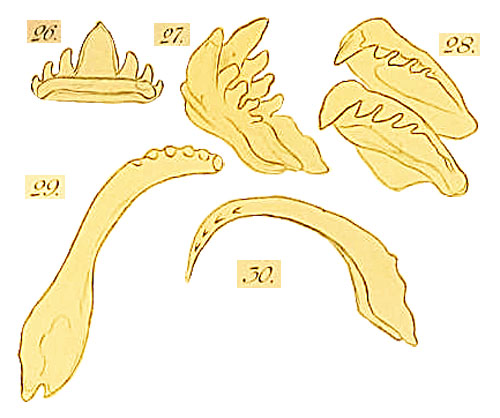

Radula of Strombus gigas in Bergh, 1895, pl. 22, fig. 26 - 30

- Bergh, 1895, p. 353, 354: "Die Mundhöhle ziemlich eng, von der Zunge fast ganz ausgefüllt. Die Zunge stark, ziemlich breit, vorn gerundet, mit Spuren von einigen ausgefallenen Zahnplattenreihen, und unten mit medianem Kamm. In der roth-braunen schillernden (3,8 mm breiten) Raspel 16 Zahnplattenreihen, die Randpartie der Raspel aber gelblich wegen der Seitenzahnplatten, die nur im obern Theile (und theilweise im Grundtheile) roth-braun waren. Unter dem Raspeldache und weiter in der Scheide fanden sich 64 entwickelte und 10 halb- und fast nicht entwickelte Reihen; die Gesammtzahl derselben somit 90. Bei dem erwähnten jüngern Individuum waren in der Raspel 19 Zahnplattenreihen vorhanden, weiter nach hinten 64 entwickelte und 6 halb- und unentwickelte Reihen; die Gesammtzahl somit 89. Die vordersten 3-5 Reihen zeigten die Platten abgerieben , beschadigt (ohne Dentikel) und theilweise ausgerissen. Das fest anliegende Raspeldach flach, ziemlich breit, zungenförmig, 3 mm lang. Die Fortsetzung der Raspel ist hinter dem Dach stark nach unten gebogen, dann wieder nach oben gekrümmt; das Ende der Raspelscheide durch einen musculösen Strang mit dem hintern Theil des Vorderendes der Zunge verbunden. Die medianen und die Zwischenplatten sind von roth-brauner Farbe, so auch die obere Hälfte der Seitenplatten sowie der untere Theil ihres Grundstücks; die Farbe der Zahnplatten, wie gewöhnlich, in der Raspelscheide dunkler. Die Breite der vordersten wie der hintersten medianen Platten betrug 0,80 mm; bei dem jüngern Individuum nur 0,52; die Breite der Zwiscbenplatten 1,1 mm. An den medianeu Platten (Taf. 22, Fig. 26) kamen an jeder Seite des mittlern Dentikels 3 kleinere vor; an den Zwischenplatten (Fig. 27, 28) ausserhalb der kräftigen Spitze des Schneiderandes 3-4, selten 5 Dentikel; von den Seitenplatten (Fig. 29, 30) trug die innere 5-6 Dentikel; die äussere ebenso, mitunter auch nur 4. - Die milchweissen Zungenknorpel 5,5 mm lang bei einer Breite von 4,5 und einer Dicke bis 2 mm; die 3/4 ihrer Unterseite dienen Muskelanheftung."

1941

Description of Strombus samba by Clench & Abbott, 1941, p. 10:

- "Shell 150 to 180 mm. in length, solid, spinose, roughly sculptured. Whorls 9 to 10, regularly increasing in size. Color of shell pale yellowish. Parietal wall and outer lip brownish yellow, merging into deep pink within the aperture. A heavy aluminum-like glaze is always present on the parietal wall and outer lip. Aperture long, comparatively narrow, slightly oblique, and with a moderately developed stromboid notch near the base of the outer lip. Basal canal short and slightly recurved. Outer lip slightly flaring and greatly thickened, the upper portion or shoulder extending above to the height of the spire. Columella short. Spire pointed. Suture rather indistinct, slightly indented, and at times overlapping the spines on the whorl above. Nuclear whorls smooth. Spiral sculpture on the first few post-nuclear whorls consists of fine striae. On the body whorl these develop into coarse thread-like lines, and in some specimens become rough corrugations. Axial sculpture on the spire often consists of pointed nodules, while on the last two whorls, moderately long spines are present. Operculum much smaller than the aperture, somewhat sickle-shaped, brown, and without saw-like teeth on its outer margin. Periostracum horny, yellowish brown, and generally covering the entire outer shell."

Types: "Holotype no. 116054, Mus. Comp. Zoöl. Wood Cay, West End, grand Bahama, Bahamas. William J. Clench collector." (Clench & Abbott, 1941, p. 11)

Clench & Abbott, 1941, p. 12: "Remarks. This species is closely related to S. gigas, though it possesses characters some-what approximating S. costatus. It differs from S. gigas by its smaller size, very much thickened and shorter lip, and by the presence of a great deal of aluminum-like glaze. The soft parts, particularly the portion extruded while crawling, are nearly entirely black, while the color of S. gigas is orange red. S. samba approximates large specimens of S. costatus in size, in thickened lip and in the presence of the aluminum-like glaze, but differs in possessing pink within the aperture, and in having at times blunt spines on the spire."

Strombus samba Clench & Abbott, 1941, pl. 8

1946

McGinty, 1946, p. 46:

- "Mr. Alpheus Hyatt Verrill, naturalist, author and artist, has turned up a Strombus which in youth has characters of both S. gigas and S. costatus, but in the adult stage is nearer to the former. We are calling it:

- Strombus gigas verrilli. Plate 5, figs. 2, 3 ; plate 6, figs. 7, 8.

- It is shorter and chunkier than gigas. In the larger immature and the adult shells the general form and proportions resemble costatus more than gigas. In the younger shells the resemblance is still stronger, many being indistinguishable from costatus except by the number of spines, the young costatus usually having from 12 to 16, whereas verrilli has from 9 to 11. S. gigas in all stages never has over 7 spines, the average being 5. In nearly all cases the spines are far shorter and more obtuse than in gigas. In the majority of the larger immature specimens, and in all the adults, the first three or four spines are reduced to small rounded tubercles or slight projections and in many specimens all the spines are mere tubercles. In a few specimens one or more of the spines on the last whorl may be almost as long as in gigas but are stouter, more curved and more obtuse, much like the spines of some specimens of costatus. Canal sharply upturned and swollen. Several conspicuous irregular tubercles on dorsal surface. In color these shells are very variable, especially in the younger specimens. The general color varies from almost pure white through lemon yellow to violaceous, rose, ochreous to brown. Most of the younger specimens and many of the larger shells have the spines marked with rich brown as in costatus. Interior surface of lip usually yellowish shading to pink or violaceous. Column varying from white to rose pink or violaceous with polished area marked with reddish brown and a blackish area. Many specimens are striped longitudinally with brown on an ashy ground while others may be banded horizontally with several shades of brownish. In specimens having the interior of lip pink the color is usually restricted to the marginal area. The animal differs from gigas in being largely orange with the darker portions olive marked with spots or rings of yellow. Mantle varies from deep yellow to orange with a black border. The difference between these shells and gigas (in all stages of growth) may best be seen by viewing them end on. The very distinct difference in the spacing of the spines is at once apparent even in those specimens having the fewest spines or tubercles. There appears to be some difference in the operculum, that of gigas averaging more slender, more curved and more pointed than in these shells. The shells were first found, Nov. 24, 1945, in a mangrove swamp near the north end of Lake Worth and, as far as known, have not been obtained elsewhere. They apparently are restricted to a small area, about half an acre in extent, and diligent search has not revealed their presence outside of this area. Neither have they been located in deep water, all specimens observed or collected having been in water less than three feet in depth. Many have been found in water so shallow that it barely covered the shells. The notes following were mainly supplied by Mr. Verrill. In their habits they differ markedly from S. gigas for while gigas lives fully exposed upon sandy or muddy bottoms, verrilli lives buried in mud on a grassy bottom, although often with the upper portion of shell exposed, and when feeding they are almost fully exposed. The larger immature, and the adult specimens are usually overgrown with large masses of algae which serve still further to conceal them. In all of our collecting in the area inhabited by these shells we have never found a specimen of S. costatus, nor a typical specimen of S. gigas. There is, however, a considerable variation in our large series of specimens, both in the length of the tubercles, the colors and the forms. Some individuals have spines almost as long as typical gigas, others may have one large spine with the others merely small knobs, still others may have only small tubercles while still others may have only indications of tubercles. In every case, however, they are readily distinguished from gigas by the number of tubercles in each whorl. Whereas gigas has from five to seven of these, verrilli has from nine to eleven, while costatus has from twelve to fourteen (but exceptionally only 9 on the last whorl). In the adults the tubercles are difficult to detect on the surface of the flaring lip and for this reason they resemble gigas more than do the immature and young specimens. The smaller, younger ones resemble costatus more than gigas, but are readily distinguished by the number of tubercles and usually by color, although, as previously stated, the colors in all stages are very variable. Some specimens (when epidermis is removed) are almost pure white, others are distinctly banded with ochreous-brown on a lighter ground, others are mottled with various shades of brownish, others are longitudinally striped; some specimens are quite pink or rosy throughout, still others are pale orchid or lilac, while others are rich yellow. In every case, however, there are rich sienna markings on the column near the lip together with patches or areas of black. In many the columellar callous surface is nearly as pink as in gigas, but in others there is no trace of pink. The inner surface of the lip also varies, some showing no pink suffusions, others being decidedly pink, others yellow, while in a few adults the entire inner surface of the lip is richly opalescent with lavender and mauve predominating. As a rule, too, each of the spiracles is tipped with sienna or chestnut-brown, this being particularly apparent in the younger specimens. The color of the animal is also quite distinctive. The anterior dorsal portion is olive or greenish-gray mottled and spotted with yellowish-white or pale yellow, tips of tentacles golden yellow, mantle and posterior portion of body rich orange, foot pinkish-gray. Sex appears to have no bearing on the size of the shells, some of the smallest adults being females while most of the larger adults examined have been males. Although the adult specimens average much smaller than the adult specimens of gigas a few very ancient, almost fossilized specimens, round buried approximately two feet beneath the surface of the mud, arc fully as large as the average adult of gigas. The presence in considerable numbers of these ancient shells, typically verrilli, would indicate thai this particular, restricted area has been inhabited by them for a very long period of time."

- t: Strombus gigas in McGinty, 1946, pl. 5, fig. 1

- b: Strombus gigas verrilli McGinty, 1946, pl. 5, fig. 2

- "Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org"

- l: Strombus gigas verrilli in McGinty, 1946, pl. 5, fig. 3, apical view of young x 2/3 (0 pl. 6, fig. 7)

- r: Strombus gigas in Mcginty, 1946, pl. 5, fig. 4 (= pl. 6, fig. 9)

- "Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org"

- Strombus costatus in McGinty, 1946, pl. 6, fig. 6, 75 mm

- Strombus gigas verrilli McGinty, 1946, pl. 7, 124 mm

- Strombus gigas in McGinty, 1946, pl. 9, 88 mm

- "Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org"

Strombus gigas verrilli McGinty, 1946, pl. 6, fig. 8; 200 mm

1947

McGinty, 1947, p. 31:

- "Strombus gigas verrilli. - Further collecting at various stations, through the past summer and fall, has permitted me to extend the range of this subspecies. It is now known to occur from Ft. Pierce, St. Lucie County, southward as far as Key West, in Florida. Occasional Bagaman specimens have been observed in local curio shops, but the extent of its West Indian distribution is as yet unknown."

Verrill, 1947, p. 32:

- "During the past month, I have collected two additional specimens of Strombus samba in Lake Worth. Both were living, and measure 155 and 197 mm. in length. I have also collected a very ancient shell of S. samba in a semi-fossil state, partially embedded in coquina, which would seem to indicate that this species has inhabited Lake Worth for a very long perios of time. I have also obtained a number of specimens of Strombus pugilis alata from a colony discovered in Lake Worth. This, I believe, is the first report of this shell on the Florida east coast."

1948

Verrill, 1948, p. 1:

- "THE STATUS OF STROMBUS SAMBA CLENCH. - There appears to be a great deal of difference in opinion in regard to the status of Stromhus samba Clench. Some conchologists consider it as merely a diseased or aberrant form of S. gigas; others regard it as merely a variety of gigas; still others think it possibly a hybrid of S. gigas and S. costatus (the native Bahaman name "samba" meaning a mixed breed), while still others feel that it is a valid species. Although samba is an abundant shell in some areas, and thousands might be obtained readily, yet it is comparatively rare in most collections and, as far as I am aware, no one has ever made a really exacting study of the shell and its habits nor bothered with the characteristics of the animal. During the past few months I have made a study of samba, having examined over 100 specimens and especially the animals in life. From these studies I am convinced that S. samba is a distinct and valid species. In the fully adult form the shell itself differs markedly and consistently from either S. gigas or S. gigas verrilli. Moreover, the animal is entirely unlike either of these species, both in color and form. Instead of having a dull olive or brownish body more or less mottled with lighter colors, the animal of S. samba is light buff with a pinkish tinge and is unmarked. The mantle is ochreous, deepening to rose or salmon near the junction with the body, and, instead of having a blackish edge, it is spotted with blackish near the outer border. The eye-stalks are pale beige spotted with brown, and are much stouter than in S. gigas or var. verrilli and are much enlarged or swollen at the base so that there is no space between them, whereas the eyestalks of S. gigas are separated by quite a wide space at their bases. Finally, the upper or dorsal surface of the foot is rich delft-blue — a most unusual and distinctive feature. The operculum also differs from that of gigas or verrilli, being relatively larger, more curved and proportionately broader, with the posterior extremity more obtuse and angular. Oddly enough, the natives of the Bahamas where samba is most abundant all maintain that they have never seen a young or a perfect shell of this species, all being massive and heavily encrusted with lime and marine growths, with the lips greatly thickened and with the enamel-like coating worn away by constant attrition, their whole appearance giving the effect of great age. That this shell should live on indefinitely is not surprising, for even the Fasciolaria tulipa (or "Cinch-killer") finds the thick shell of S. samba impenetrable, while the natives of the island consider the meat inedible. Hence the shells are seldom taken or disturbed. However, I have discovered that the mystery of the absence of less senile or perfect specimens of S. samba is really no mystery at all, the explanation being that such shells are scarcely distinguishable from the same size specimens of S. gigas by a cursory examination. But they are readily distinguished, both by the distinctive blue foot which is present in all specimens, and by the far heavier, thicker shell and the form of the aperture. In these younger, perfect specimens the lip usually is extended upward in a trough-like form and has a handsomely fluted or ruffled edge. The dorsal surface is much rougher than in S. gigas, with numerous conspicuous tubercles and with a shoulder or ridge near the lip. The transverse grooves, extending from the lip, are much more pronounced and deeper than in gigas or verrilli. Usually, too, one of the dorsal spines of the last whorl is much longer and wider than the others and is proportionately more massive than in gigas of the same size. All the spines are flattened rather than rounded as in gigas. Once one is familiar with the specific characteristics of these shells one may recognize S. samba at a glance, and while some may resemble S. gigas more than others the blue foot is always a distinguishing and unmistakable means of identification. Up to the present time, I have been unable to obtain (or to recognize) the immature and very young shells of S. samba. All the perfect specimens I have collected are fully adult. Perhaps the blue foot does not develop until the shell reaches the adult stage and immature specimens may be indistinguishable from those of S. gigas externally."

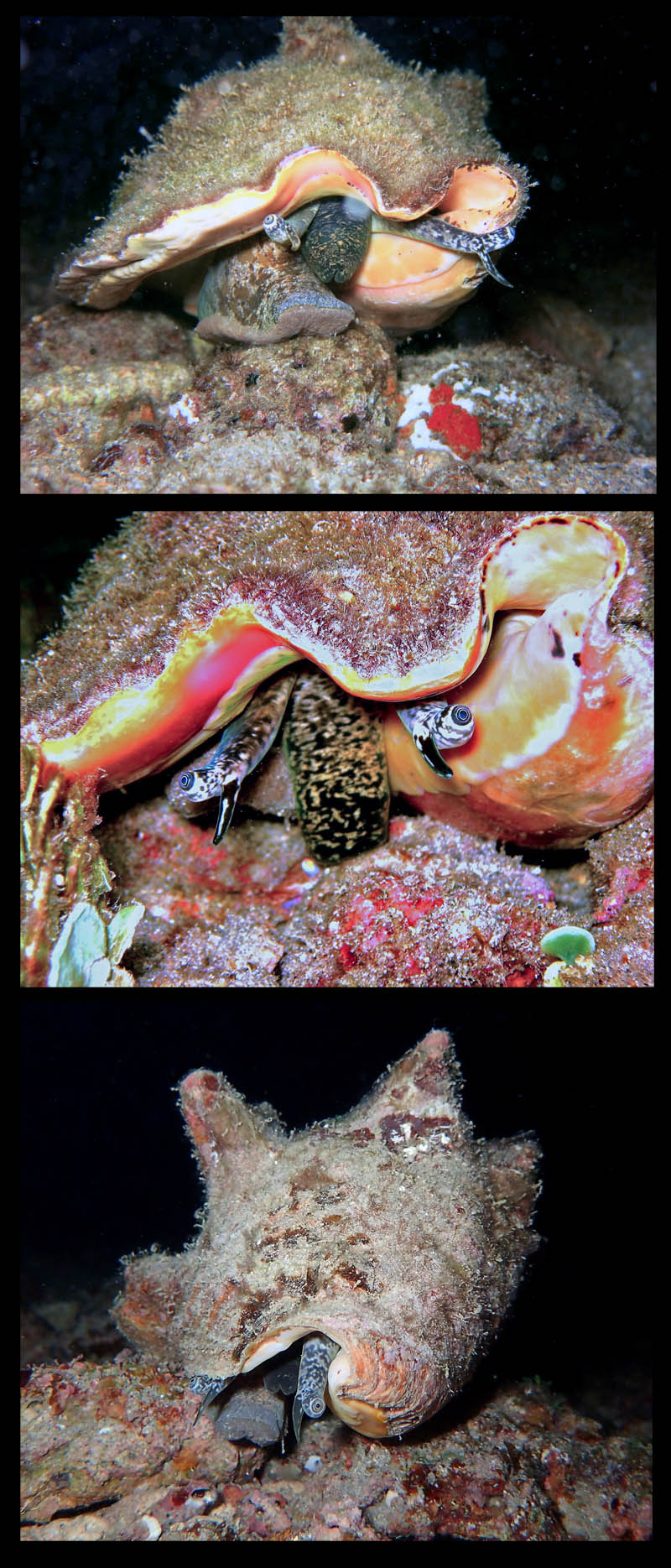

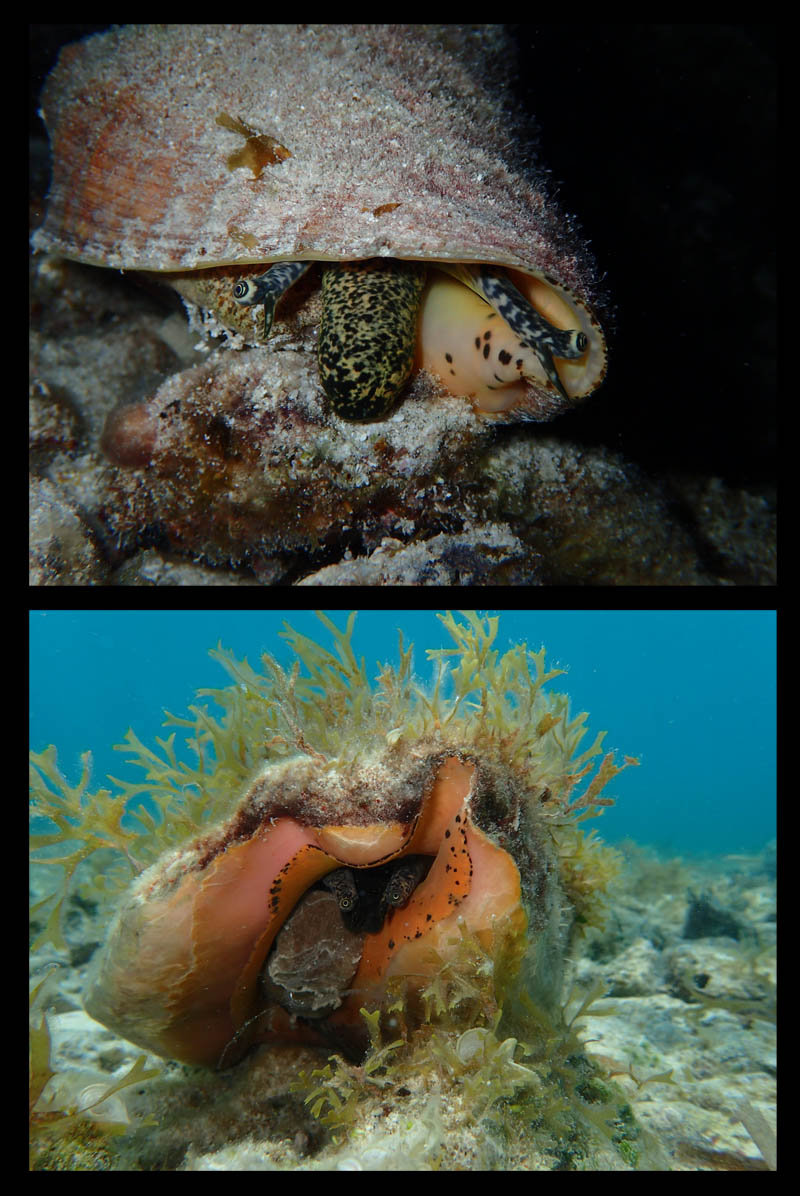

Breder, 1948, p. 302:

- "One species is largely, if not entirely, confined to close association with these conch beds. The inquiline association of this species, Astrapogon stellatus (Cope), within the gastropod Strombus gigas Linnaeus is well known (Plate, 1908; Hildebrand and Ginsburg, 1926; Gudger, 1927, 1929), but there appears to be no data on its frequency of occurrence, or on its variation as associated with habitat. (...) In contrast to this ratio of one fish to fewer than 12 conchs, a collection of Strombus samba Clench made outside the harbor a little east of Turtle Rock August 25, consisting of 319 conchs, was found to contain not a single fish. If the same ratio of conch to fish existed here as in the harbor about 20 fish should have been recovered. Evidently either this association is chiefly, if not entirely, characteristic of the inside banks at this place, or it is a matter of specificity."

Breder, 1948, p. 309:

- "The fish Astrapogon, inquiline in Strombus gigas, shows an approximately equal infestation of this mollusk irrespective of the concentration of the latter, but only in inside sheltered waters, and it is evidently absent from the relatively unsheltered Strombus samba. About one Strombus in 12 was found to be inhabited by an Astrapogon in sheltered places."

1978

Strombus gigas in Javidpour, 1978, pl. on p. 103,

- 1.r: fig. 1, 3 USNM no. 244729

- 2.r: fig. 2, 7 USNM no. 244730

- 3.r: fig. 4, 5 USNM no. 244731

- 4.r: fig. 6, 8 USNM no. 244732

- "Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org"

1989

Mitton, Berg & Orr, p. 359:

- "In Belize, we collected samples of both normal conch and samba, a smaller, melanic form that is generally shunned by fishermen because ofits size and dark meat. Allelic frequencies are similar for these samples for all loci except Gdh. Table I presents the sum of alleles 1 and 2, but the frequencies of these alleles differ between the morphs. For samba, the frequencies (and standard errors) of alleles 1, 2, and 3 are 0.22 (0.06), 0.02 (0.02), and 0.76 (0.06), while the corresponding frequencies for the normal conch are 0.00, 0. 17 (.05), and 0.83 (0.05). The samba and the normal conch do not appear to be random samples from a randomly mating population (P < 0.01). We also sampled samba from French Cay, but all of the mature animals obtained were samba, so we could not replicate the comparison of normal and samba conch from Belize. Samples from other localities in the Turks and Caicos contain only normal conchs. There are differences between French Cay and the other Cays in the Turks and Caicos, especially at Gdh and 6Pgd, but these might be attributable to microgeographic variation rather than differentiation of normal and samba conch."

1992

Berg et al., 1992, p. 437 about Strombus gigas in Bermuda:

- "Queen conch, however, were only observed breeding near the edge of the reef platform (North Rock, mouth of Castle Harbor) where ocean currents would tend to carry larvae away from the platform."

1994

Strombus gigas pahayokee Petuch, 1994

Original Description of Strombus (Eustrombus) gigas pahayokee by Petuch, 1994, p. 82:

- Strombus (Eustrombus) gigas pahayokee Petuch, n.sp. [sic]; Holotype; Length 187 mm. HL; from Griffin Bros. pit, Holey Land area, Palm Beach Co., Florida, USA

- Holotype

2003

Johnson, 2003, p. 22:

- "samba Cl, Strombus 1937, Proc. N. Engl. Zool. Club, 16: 18, pl. 1, fig. 1 (Wood Cay, West End, Grand Bahamas Island, Bahamas); holotype MCZ 116054."

2008

Some notes on the ontogeny, ecology and shell of Strombus gigas LINNAEUS, 1758, the Queen Conch from the Caribbean Sea by Klaus Bandel

This short rundown on the life history of Strombus gigas is based partly on own observations and confirmed and expanded by the intensive studies on culturing the species by DAVIS (2005). Some references from the literature are included. About the species many informations including illustrations of shell can be obtained from various sources in the internet, for example Eddie Hardy.

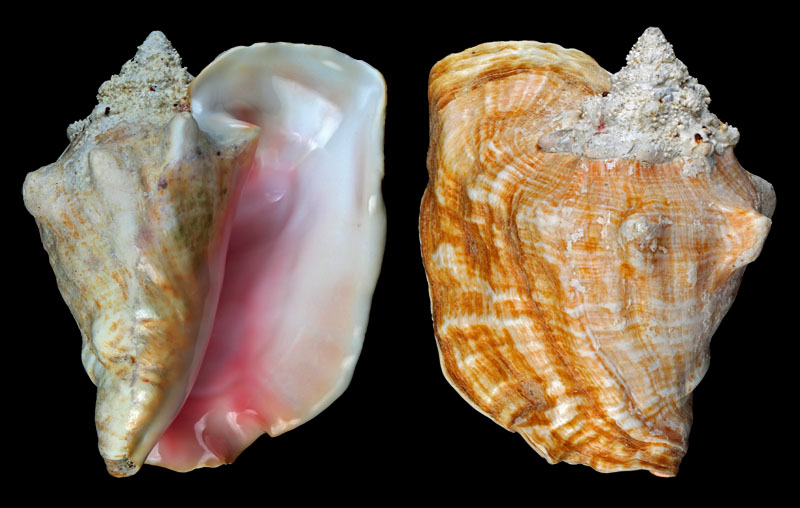

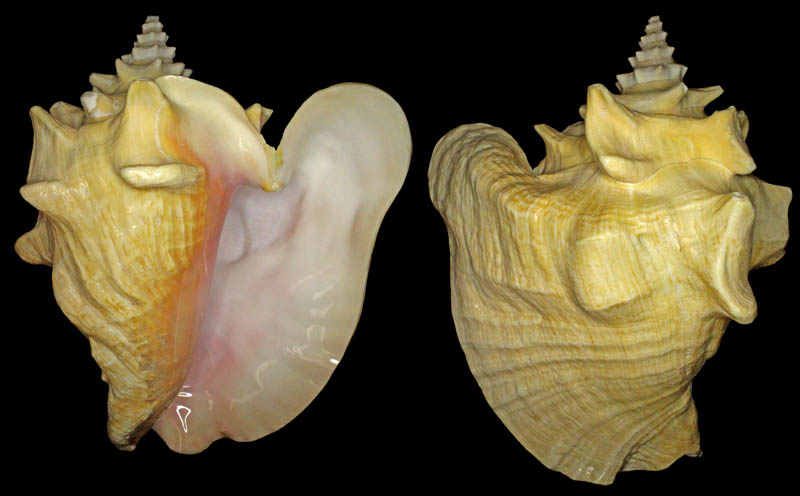

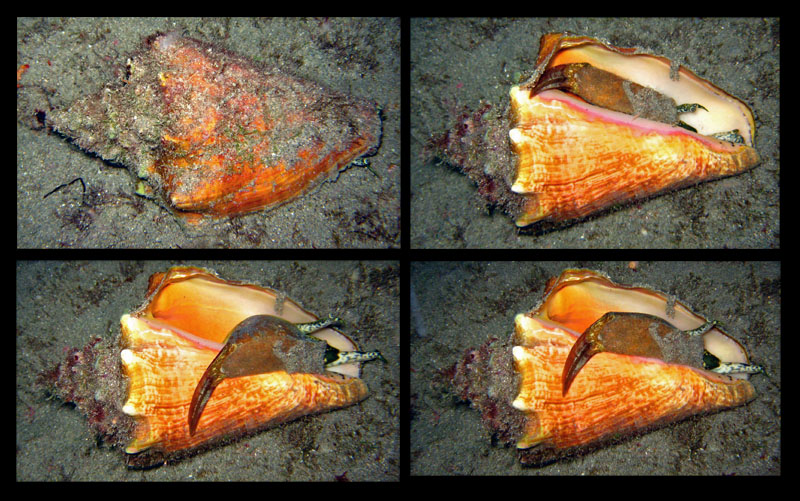

The large shell of Strombus gigas is characterized by its large and flaring outer lip and the rich shades of pink, yellow and orange in the aperture (ABBOTT 1974). Periostracum is thick and flakes of from dried shells. The large shell is over 20 cm high, may be even up to 35 cm high. It gets heavy with age. The outer lip is wide, flared and thickened, sometimes with undulating margin in front and with a frontal sinus, the stromboid notch. A wide open and short siphon canal is developed. Through it and the stromboid notch the animal stretches its eyes when not buried in the sand. The posterior end of the flaring outer lip is attached to the spire on the shoulder of the last whorl next to a spine bearing corner. A wide low sinus forms the apical margin of the outer lip. Often this part has a bump on its outside, where it connects to the last rounded node on the body whorl. The seven whorls of the spire before the last have a corner on which a row of low pointed spines is aligned.

Other than Turbinella angulata (LIGHTFOOT, 1766), Strombus gigas is the largest gastropod in the area of Santa Marta in the shallow Caribbean Sea (BANDEL & WEDLER 1987). In the shallow sea grass beds of Florida, the Bahamas and Bermuda the queen conch is even the largest gastropod (CLENCH & ABBOTT 1941, ABBOTT 1974, RANDALL 1964). Juveniles have a thin fragile outer lip and prefer very shallow lagoonal areas with soft substrate and dense turtle grass in which they can hide. Due to the culture of individuals it is well known what time is needed by them to grow to a size in which the adult aperture forms. To turn into a mature individual that can reproduce Strombus gigas has to live three to four years. It is ready to reproduce only after the outer lip has fully flared (DAVIS 2005).

Large and fully grown individuals move to deeper water and prefer sea grass bottoms in 1.5 to 5 of depth in the bays near Santa Marta. Old shells are commonly strongly encrusted with all types of sessile organisms, including heavy corals. Such heavy overgrowth on the shell characterize individuals which live near the reef and on reef debris. Where the bottom is soft old individuals still bury themselves totally in the sand when resting. Due to this repeated process of burying the outer shell surface slowly becomes eroded by the sand and this is compensated for by deposition of shell material to the inner surface of the shell. In very old individuals the shell has become thickened from within and corroded from the outside resulting in a small and heavy individual which is known as Strombus samba CLENCH, 1937. It is assumed that individuals of Strombus gigas may be able to live for up to 30 years.

Adult individuals usually stay away from the surf, except when spawning. They move into the breaker zone and deposit their egg masses of up to halve-a million eggs within the oxygen rich water just below tide line (BANDEL 1976). The embryos which develop within their round individual egg case hatch after four days (ROBERTSON 1959). Sexes are separate and in natural population males are a little smaller than females, and both are present in about the same number (DAVIS 2005). First copulation in Strombus gigas with sexually mature individuals occurs when the animals are about four years old. The thin sticky strand of eggs is covered with sand grains, and egg masses form large sausage- like bodies (DAVIS 2005, fig.3). The veligers hatch with two lobed velum and actively swim in the water column for about three weeks. Here they feed on phytoplankton. They metamorphose into benthic animals in response to signals which they receive from the sea grass habitat.

The egg masses are deposited on or just below the surface of the sediment. A whole population of a single bay near Santa Marta was encountered in the process at the same time of the year (BANDEL 1976). Copulation and spawning usually occurs when water is warmest (DAVIS 2005). The egg capsules are interconnected to a gelatinous string of about 1 mm in thickness (BANDEL 1976, fig.1), which in case of Strombus gigas is several meters long and tangled to a heap (D’ASARO 1965). Each capsule contains one embryo, and from one spawn about 300000 veligers to as many as 750000 hatch.

The larva of Strombus gigas hatches as two lobed veliger, after four days in the Plankton has four lobes, and after about 8 days is has 6 lobes (DAVIS 2005, fig.7). Metamorphosis occurs when the fully grown protoconch is about 1.2 mm high and the larva has been in the Plankton for at least 21 days. After 8-10 days a six-lobed velum is present when the shell is about 0.7 mm in size. This velum remains similar until the larva is ready for metamorphosis with about 1.2 mm large shell. At this stage the eyes have migrated outward, the tentacles are of equal length, the pigment of the foot changes, the ctenidium (gill) becomes functional and the buccal mass has developed. In the larva ready to change to benthic life the buccal mass with the radula is present, while the veliger feeds on algal cells that have been collected by the cilia of the velum, and food reaches the stomach by way of ribbons of cilia. When the veliger has metamorphosed the velar lobes are lost. The foot which had only been used to manipulate the operculum is now used for crawling, and the small snail searches for food with the proboscis. In about half a year the young will have grown up to a size of about 20 mm, but growth can be much less to only about 5 mm (in culture) (SHAWL & DAVIS 2004).

Larvae of Strombus gigas closely resemble those of Strombus gibberulus LINNÉ, 1758 (Strombus gibberulus albus MÖRCH, 1850) and Strombus fasciatus BORN, 1778, both of which are very common in the Red Sea (BANDEL et al, 1997 Fig.2; Fig.18, A-D). Also regarding the steps of the transitions from larval to adult organs during metamorphosis resemble each other.

In case of Strombus gigas, after feeding on phytoplankton for about three weeks (up to eight weeks, DAVIS 2005) during larval existence metamorphosis to bottom life results in the 1.2 mm large benthic animal that hides in sandy bottom and algal thickets, usually within the sea-grass meadows. In Santa Marta small juveniles were found hidden in algal thickets and in shallow sea grass meadows often within the intertidal zone of a lagoon. DAVIS (2005) found that the life usually spans for about 6 years and sometimes up to five times longer. Juveniles have a thin apertural margin and elongate conical shape. Their hidden life ends with the formation of the final aperture. After that individuals may remain for a longer time on the surface of the bottom substrate and can have heavy overgrowths. Mature Strombus gigas individuals prefer the well illuminated zone in shallow water, where they graze diatoms and other organisms on algae. The food of Strombus gigas consist predominantly on minute algae. When they feed quite a lot of sand is swallowed, which results in the production of many feces with characteristic shape (BANDEL 1976).

They are usually in association with "turtle grass" (Zosteraceae). Locomotion of adults is characterized by leaps, while juveniles move with the usual gliding of their foot as is the usual case among other benthic gastropods.

Grown Strombus gigas moves by anchoring the foot in the ground with the pointed operculum and than pulling the body up and forward in one jump. Than disengaging the anchorage and forming a new one in the direction of wanted movement and so on.

The eye and the tentacle belonging to it peering through the siphonal notch is larger than the one extended through the stromboid notch to the right of it. During locomotion the tentacle and eye is held above the apertural edge and searches through the water. When the snail is attacked by a star fish of a carnivorous gastropod such as Fasciolaria it will shoot out the saw edged operculum and swipe it across the shell to loosen the offending grip. When placed on the sand on its back the snail brings out the narrow and muscular foot, anchors the claw-like operculum in the bottom sediment and turns itself over in a second (ABBOTT 1960, BANDEL & WEDLER 1987).

Live animals with their eyes protruding from below the shell are also documented by internet pages, such as of R. Dirscherl.

2011

Allmon, 2011, p.2:

- "Petuch (1994) names and figures a holotype for a new subspecies, Strombus gigas pahayokee (although it is labeled as “n. sp.” [p. 82]), but he does not include a description of the taxon."

2014

Duarte et al., 2014 reported Lobatus gigas from the coast of Paraiba State, Brazil.

Specimens from institutional collections

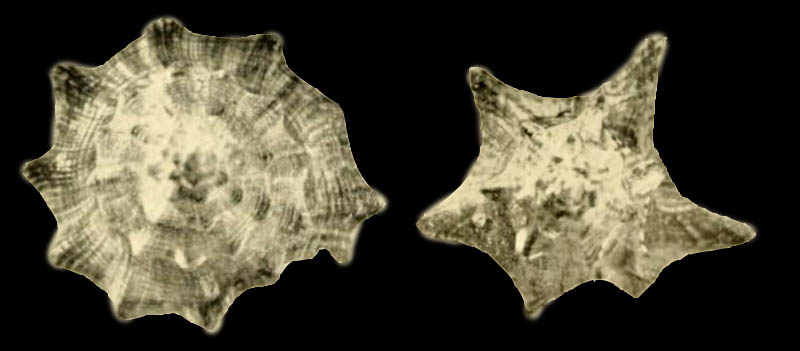

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Miocene? / Pliocene?, Bowden-Formation; St. Thomas, East of Port Morant (type locality of Bowden Formation), Jamaica; Ex-coll. P. Jung, 1969

Coll. Naturhistorisches Museum Basel no. H16610, (hypotypoid for Jung, 1971, Strombus gigas, Nautilus 84(4), 129, Fig.1); Photo Virgilio Liverani

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Neogene; Rio Yaque del Sur, Dominican Republic; Coll. Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, loc. no. 16898; 77 mm; Ex-coll. PJ 1652

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Coll. Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, loc. no. 18744; Photo Virgilio Liverani

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Pliocene/Pleistocene; Punta Arenas, Isla Margarita, Venezuela; Coll. Stichting Schepsel Schelp no. SSS58567

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Pliocene/Pleistocene; El Yaque, Isla Margarita, Venezuela; Coll. Stichting Schepsel Schelp no. SSS58488

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Tamiani Formation, upper Pliocene; Naples Quarry, Collier County, Florida, USA; 250 mm; Coll. Stichting Schepsel Schelp no. SSS16302

Lobatus cf. gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Tamiani Formation, upper Pliocene; Naples Quarry, Collier County, Florida, USA; Coll. Stichting Schepsel Schelp no. SSS16302

Specimen from private collections

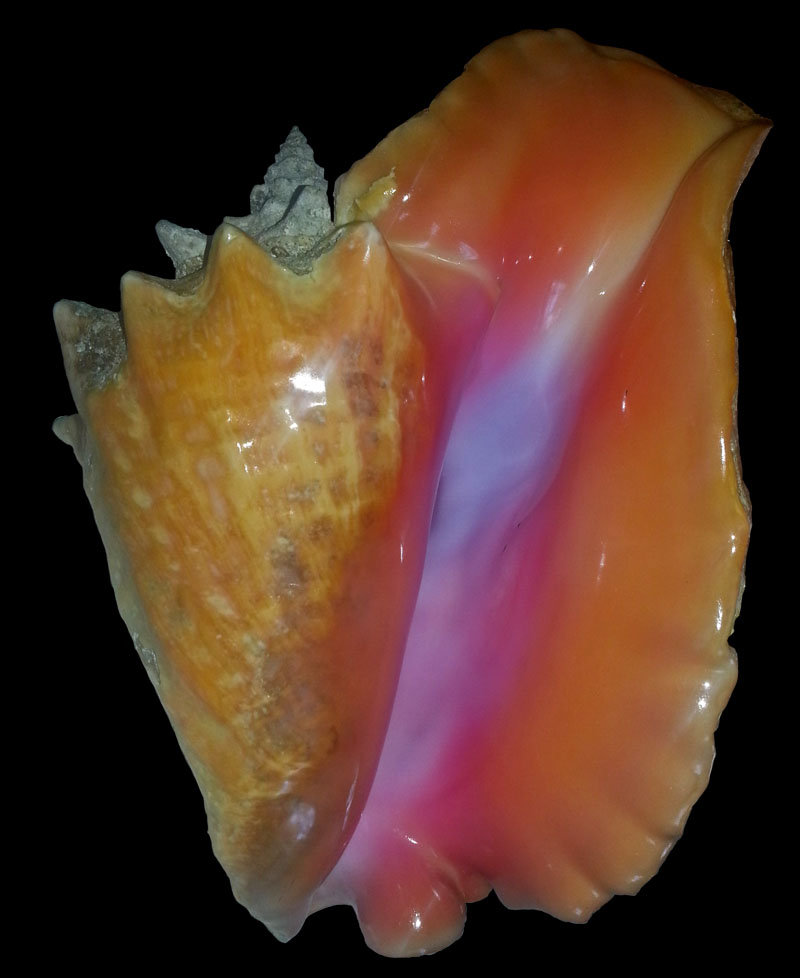

Strombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Content Key, Monroe County, Florida, USA; Coll. Gijs Kronenberg no. 328

Strombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); off Santa Cruz del Norte, Cuba; collected by diver 10 m deep; 1987; Coll. Roman Fankhauser

Strombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Key West, Florida, USA; 1993; Coll. Roman Fankhauser

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Ragged Island, Jumentos Cays, Lucayan Archipelago, The Bahamas; 270 mm; Coll. Heiko Lärtz

- rare colour form with yellow aperture

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Ragged Island, Jumentos Cays, Lucayan Archipelago, The Bahamas; 280 mm; Coll. Heiko Lärtz

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Ragged Island, Jumentos Cays, Lucayan Archipelago, The Bahamas; 280 mm; Coll. Heiko Lärtz

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Ragged Island, Jumentos Cays, Lucayan Archipelago, The Bahamas; Coll. Heiko Lärtz

Strombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); dwarf; Eleuthera Island, The Bahamas; in about 15 ft. of water in Thalassia beds; 165 mm; Coll. Dennis Sargent

Strombus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); dwarf; Florida Keys, Monroe County, Florida, USA; farm raised specimen; 144 mm; Coll. Dennis Sargent

Strombus gigas forma horridus; Coll. Koenraad De Turck

Strombus gigas forma horridus; Coll. Koenraad De Turck

Strombus canaliculatus Burry, 1949; Photo Dennis Sargent

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Bermont Formation, middle Pleistocene; South Bay, Palm Beach County, Florida, USA; Coll. Antoine Heitz no. 1747

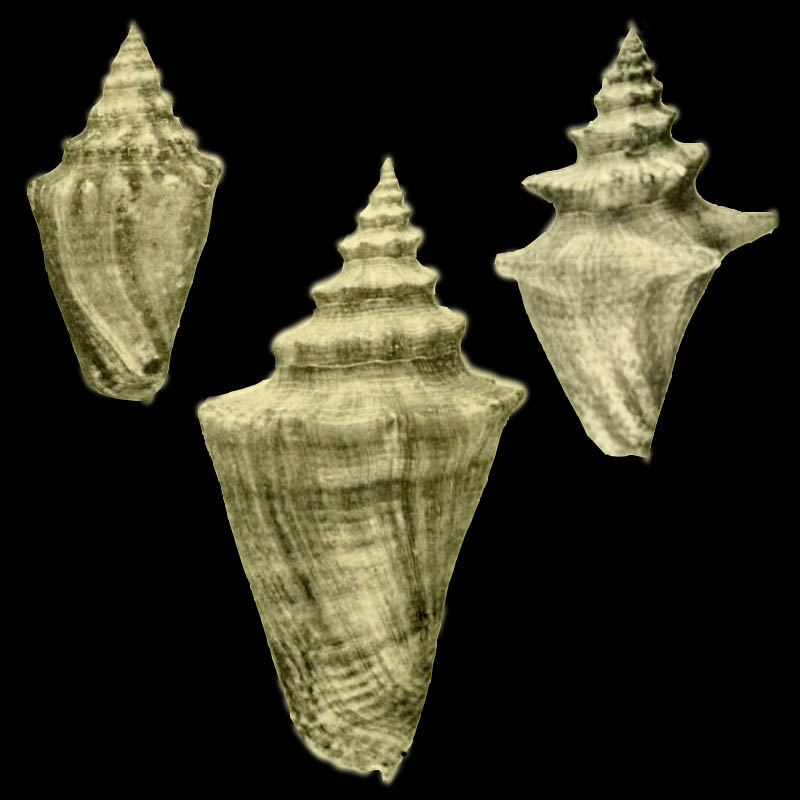

Lobatus gigas pahayokee Petuch,1994; Holey Land member, Bermont Formation, middle Pleistocene; Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, Florida, USA; 195 mm; Coll. Ulrich Wieneke

Lobatus gigas pahayokee Petuch,1994; Holey Land member, Bermont Formation, middle Pleistocene; Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, Florida, USA; 175 mm; Coll. Ulrich Wieneke

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Juvenile; upper Pliocene; Palm Beach Pit, Loxahatchee, Palm Beach County, Florida, USA; 180 mm; Coll. Martin Duckstein

Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758); Juvenile; upper Pliocene; Palm Beach Pit, Loxahatchee, Palm Beach County, Florida, USA; 147 mm; Coll. Martin Duckstein

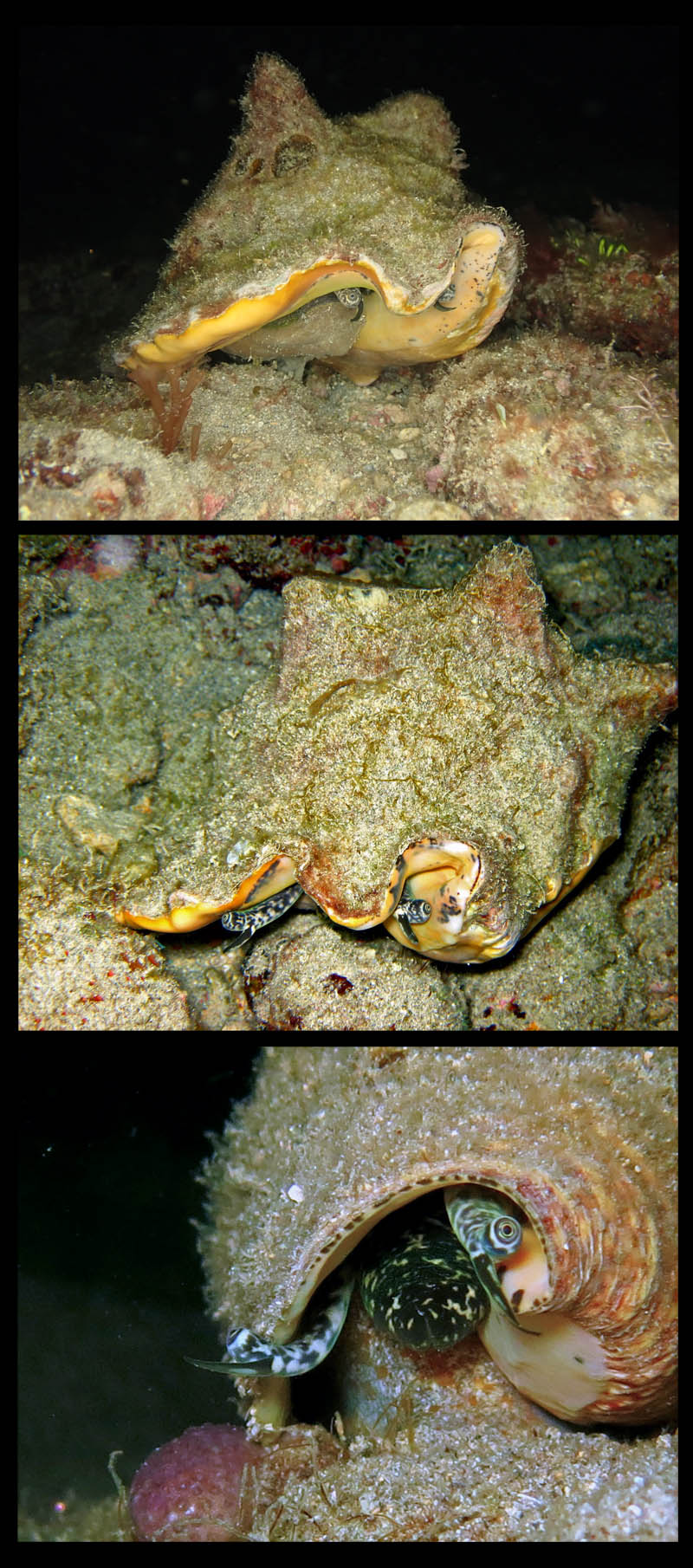

Living Strombus gigas

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Pompano Beach, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Key Largo, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Key West, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Bahamas, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik, Marathon, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik SCUBA diving, at 3-4 m; Pompano Beach, Broward County, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik

Photos of juvenile Strombus gigas; taken by Anton Oleinik SCUBA diving, at night in 10 feet of water off Fort Lauderdale, Broward County, Florida, USA; Copyright Anton Oleinik.

- Comment Oleinik, 2010: "Pictures show very well how the animal is capable of retracting itself into the shell and shows the foot and operculum which the animal uses for jump-like locomotion."

Film

Sequences

Internet

References

- Allmon, W.D., 2011, Review of: “Molluscan Paleontology of the Chesapeake Miocene", by Edward J. Petuch and Mardie Drolshagen, 2010: PALAIOS 2011, p. 1-4, DOI : 10.2110/palo.2011.BR64, URL

- C.J. Berg, F. Couper, K. Nisbet & J. Ward, 1992. Stock assessment of Queen Conch, Strombus gigas, and Harbour Conch, S. costatus, in Bermuda; Proc. Gulf Caribb. Fish. Inst., 41:433-438, Fulltext

- Bouvier, E.L. 1887. Systeme nerveux morphologie générale et classification des gastéropodes prosobranches; Annales de Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie 3(1):1-510, pls. 1-19

- Breder, C.M. Jr. 1948. Observations on coloration in reference to behavior in tide pool and other marine shore fishes. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 92: 281-312.

- Burry, L.A., 1949. A new Strombus species. Shell Notes 2 (7-9): 106-108.

- Campton DE, Berg CJ, Robison LM, Glazer RA, 1992. Genetic patchiness among populations of queen conch Strombus gigas in the Florida-keys and Bimini. Fish Bull 90:250–259.

- Clench, W. J. 1937. Descriptions of new land and marine shells from the Bahama Islands. Proceedings of the New England Zoölogical Club 16: 17-26, pl. 1.

- Clench, W. J.; Abbott, R. T. (1941)

- Clerveaux, W., A.J. Danylchuk & V. Clerveaux, 2005. Variation in queen conch shell morphology: management implications in the Turks and Caicos Islands, BWI. Proceedings Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute 56:715-724. URL

- Delgado, G. A., R. A. Glazer and N. J. Stewart (2002) Predatorinduced behavioral and morphological plasticity in the tropical marine gastropod Strombus gigas. Biol. Bull., 203, 112-120.

- R.C.S. Duarte, E.L.S. Mota & T.L.P. Dias. 2014. Mollusk Fauna from shallow-water reef habitats of Paraiba coast, northeastern Brazil; Strombus 21(1-2): 15-29.

- M. Javidpour, 1978. Fossil Strombus gigas from Southern Florida, The Nautilus vol. 92, p. 102-104, fulltext

- R.I. Johnson, 2003. MOLLUSCAN TAXA AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES OF WILLIAM JAMES CLENCH AND RUTH DIXON TURNER Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool., 158(1): 1–46, fulltext

- Jung, P. 1971. Strombus gigas Linnaeus from the Bowden Formation, Jamaica; The Nautilus 84(4): 129-132, Fulltext

- Little, C. (1965). "Notes on the anatomy of the queen conch, Strombus gigas". Bulletin of Marine Science 15 (2): 338–358

- McGinty, T. L. 1946. A new Florida Strombus, S. gigas verrilli. The Nautilus 60: 46-48, pls. 5-6, fulltext

- McGinty, T. L. (1947). Strombus gigas verrilli, extension of range. Nautilus, 61, 31-32, fulltext.

- Mitton, J. B., Berg, C. J., & Orr, K. S. (1989). Population structure, larval dispersal, and gene flow in the queen conch, Strombus gigas, of the Caribbean. The Biological Bulletin, 177(3), 356-362. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/1510345

- Petuch, E.J., 1994, Atlas of Florida Fossil Shells (Pliocene and Pleistocene Marine Gastropods): The Graves Museum of Archeology and Natural History, Dania, Florida, with Chicago Spectrum Press, Evanston, Illinois, 394 p.

- Randall, J. E. (1964). Contributions to the biology of the queen conch, Strombus gigas. Bulletin of Marine Science, 14(2), 246-295.

- Smith, M., 1940. World-wide sea shells. Illustrations, geographical range and other data covering more then sixteen hundred species and sub-species of molluscs (…) together with two articles. i-xviii + 1-139. Tropical photographic laboratory, Lantana, Florida.

- Stager, J. C. Chen., V., 1996. Fossil evidence of shell length decline in queen conch (Strombus gigas L.) at Middleton Cay, Turks and Caicos Islands, British West Indies. Caribbean Journal of Science, 32(1), 14-20.

- C.P. Titley-O'Neal, D.J. Spade, Y. Zhang, R. Kan, C.J. Martyniuk, N.D. Denslow & B.A. MacDonald, 2013. Gene expression profiling in the ovary of Queen conch (Strombus gigas) exposed to environments with high tributyltin in the British Virgin Islands; Science of the Total Environment 449 (2013) 52–62.

- A.H. Verrill, 1947. Additional Strombus samba (Clench) from Florida. Nautilus, 61, 32, fulltext.

- Verrill, A.H. 1948. The status of Strombus samba Clench. The Nautilus 62(1): 1-3, fulltext

- Zans, V.A. & Lewis, C.B. 1954. Note on the occurrence of Strombus samba in Jamaica. Nat. Hist. Notes, No. 66, p. 102

|